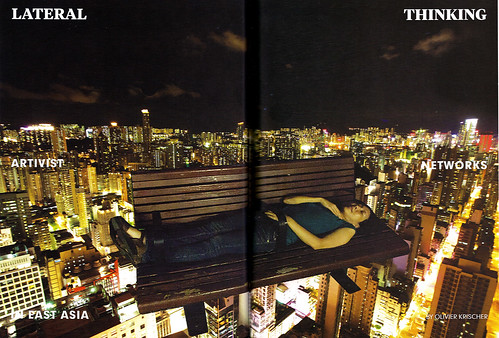

artasiapacific | MARCH/APRIL 2012 | ISSUE 77

by OLIVIER KRISCHER

Walking through Hong Kong’s Yau Ma Tei neighborhood in the

heart of the urban development on Kowloon peninsula, one is only a few subway stops from the cosmopolitan Central business district across the harbor, the financial hub of Asia. Here, the dense apartment blocks, wrapped in signboards, iridescent Chinese characters and bamboo scaffolding, appear more like collages than architecture.

The simplified map on a smart-phone screen seems hopelessly

oblivious to the thick, bustling life on the streets. Shanghai Street is far from the commercial strip of the local art scene; nor is it a site for trendy warehouse annex spaces or young upstarts, nibbling at the fringes. So, what kind of an art space would live here, and why?

In many respects, Hong Kong is similar to Tokyo, Seoul and Taipei, cities that have grown enormously in neoliberal economies of the “Asian miracle.” In these East Asian megalopolises, alongside a nascent infrastructure of commercial galleries and official institutions developed over the last 20 to 30 years, alternative and independent cultural spaces have established themselves as platforms for social resistance and creative possibility. Faced with constant “urban renewal,” often at the expense of local heritage and individual livelihoods, young artists, in particular, are often forced out of the city center or popular districts by rising property values, even when art’s very presence has added luster to the local real estate.

Despite their different contexts, artists such as Lee Chun Fung, managing director of Hong Kong’s Woofer Ten art space, Misako Ichimura, an independent “homeless” artist based in Tokyo, and Kim Kang and her husband Kim Youn Hoan at LAB39 in the Mullae Artist Village in Seoul, for example, share common concerns about the direction of urbanization in their cities, the collusion of governments and property developers, the loss of civic values and the fragmentation of local identity. Many are using art and activism, which they dub “artivism,” to be stakeholders in the cultural life, and future, of their cities; and they recognize that their local experience resonates elsewhere in the region.

The summer night in Yau Ma Tei is muggy, but the room at Woofer Ten art space is packed. The speaker is Misako Ichimura, invited as an “Artivist in Residence.” A graduate of the prestigious Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music (now Tokyo University of the Arts), she has chosen to live in a homeless community of some 40 makeshift blue tents in a corner of a park in central Tokyo since her return from Amsterdam in 2002, where she lived in a squat. As part of her ongoing projects, she and other residents run a “café” in the park, not as a business, but as a place to socialize. In an information sheet, the artist explains: “This café is also a place where homeless people and those

with homes can meet. In this community the superfluous items of

the city are collected, split and exchanged between residents, such that ‘things’ become tools of communication. This kind of system, unrelated to money, is also carried out at Café Enoaru. Every Tuesday a painting and drawing gathering is held here too. Pictures drawn here are later exhibited at Café Enoaru. Exhibitions are held many times throughout the year.” (In Japanese, “e-no-aru-café” sounds like

“the café with paintings.”) Besides these gatherings, Ichimura has

also started a group specifically for homeless women, to share their experiences and gain strength in numbers. Based on these informal meetings, in 2006 she published an illustrated book reflecting on the condition of homeless women in Tokyo, as Chocolate in a Blue-Tent Village: Letters to Kikuchi from the Park.

As part of her two-week residency in Hong Kong, in addition

to presentations discussing her experience of homelessness,

Ichimura also displayed materials from activist projects. For her

end-of-residency exhibition, she filled the Woofer Ten space with a documentary video, printed pamphlets and photos, and painted the walls with activist slogans—the largest reading “Hands off Miyashita Park!” in Japanese, in thick, frantic black letters on a bright red wall. The “exhibition,” a kind of reportage, referred to Ichimura’s efforts to organize protests against a deal between Nike and Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward that would have given naming and development rights to the public Miyashita Park to the sporting-goods giant—without any public consultation. Protests had stalled the project beginning in 2008, after which, in early 2010, artists, activists and social workers occupied the

park in a movement called “Artist in Residence Miyashita Park” (aka AIR Miyashita Park), using blogs and social media to publicize their activities and raise public awareness. Besides the commercialization of public space, the development meant 30 homeless park residents would be forced to leave. Eventually, over 100 police, including riot specialists, secured the park, removing protestors and park residents, on behalf of the company and local authorities. Although Nike subsequently agreed not to rename the park “Nike Park” as intended, plans went ahead apace, and the skate-park opened last April—as a paid, fenced-in skateboarding facility, technically run by the company on a ten-year lease from the local government.

In the face of government and corporate power, and a largely

disinterested public, can art “make a difference”? And is this the goal of activist artists? When we hear about “engaging” communities at international exhibitions, few would have the homeless, for example, in mind. Yet Ichimura never suggests that she sees the community itself as a problem, or that her art and activism—difficult to separate in practice—could take people off the streets. As her Café Enoaru project and art classes demonstrate, she has not been trying to reform the community or gentrify it with “culture.” If anything, much of her work and activism is aimed in the other direction: at the mainstream society which surrounds this community, with little or no knowledge of the issues it faces. For instance, Japan tends to see itself as predominantly middle class, yet in 2009, when Yukio Hatoyama’s new left-of-center government (one of the first changes of power in postwar Japan’s 50-plus years of democracy) published official statistics, around 15 percent of the country was revealed to fit the “working poor” bracket.

This was in sharp contrast to the national mythology, and suggested that such social issues do exist but are seldom acknowledged by the government or the general public. Whether as artist or activist, Ichimura sees her presence as a bridge between sectors of the community that do not usually meet. And for this, art can be a tool. Similar efforts have been underway in Seoul, with a level of organic collaboration that, for the time being, is changing the direction of urban redevelopment in Seoul’s Yeongdeungpo-gu district. The main forces behind Mullae Artist Village are artist-activists Kim Kang and her husband Kim Youn Hoan, who have made a career using community-orientated projects that confront specific cultural, social and political issues. After going to France to study in 2001, as with Ichimura, the Kims became involved in squatting, with Kim Kang eventually writing a thesis (in French) on the history of squatting in France. Moving back to Korea in 2004, the pair established a group called Oasis, and undertook numerous creative interventions, in Seoul and elsewhere, around various social issues.

As part of their “Oasis Project,” they set their eyes on a building

owned by the country’s largest arts association, the Federation of

Artistic and Cultural Organizations of Korea, originally established in 1961, which has built close ties to previous conservative governments over the last five decades. In 1996, the federation lobbied for funding to construct a 25-floor building in downtown Seoul, ostensibly for artists. By 2004, the building had been left incomplete for nearly seven years, apparently because government-allocated money (around KRW 16.5 billion, or USD 14.8 million) for construction had been used elsewhere by the association, and because disputes had formed with

the construction companies. “We thought of this building as a symbol of bad politics and cultural policy,” explained Kim Kang confidently, in our conversation at Mullae late last year. “We thought: Our government wanted to build this building for artists; we are artists, so we have a right to use it.”

With an impressive level of organization, Oasis raised public

awareness of their project by publicizing online their intentions to occupy the building, conducting a squatting workshop, then

circulating a mock real-estate announcement offering free studio

space on the condition that artists collaborate as a community.

They also carried out site visits of the incomplete building. The arts association alleged that Oasis were “swindlers,” charges that were quashed when authorities determined Oasis had not solicited any payments and hence had not acted unlawfully. Finally on August 15, 2004, in a well-orchestrated operation, the group moved into the building, accompanied by cameramen from the three main television channels at the time, while a band of supporters looked on from the street outside. Although only there for half a day, the group continued to organize subsequent performances at that site and elsewhere in the city. Although the Kims were eventually fined500,000 ($450)

for the action, the accompanying media attention sparked a public debate on cronyism and the lack of accountability involved in large government grants. As far as Kang is concerned, the temporary occupation was successful, as it revealed, she states coolly, “the monopoly of space in the capitalist system.”

While the “Oasis Project” targeted the relationship between

the official art world and the government, the artist’s village at Mullaedong has developed more organically. After Oasis was dissolved in 2007, the Kims became interested in this area, known for its small metal workshops, of which only a few were still in operation, as plans to redevelop the area on par with its surroundings discouraged landlords from investing in maintenance. In some cases, premises had been left empty for years. Attracted by the cheap rent, the Kims moved in, around June of that year, promptly launching their office as LAB39 – Urban Society and Art Research Center. They encouraged

other artists to seek out cheap studio spaces at the site, and the

community began to grow.

In the nearly five years since its establishment, LAB39 has held

collaborative art projects with universities, and given tours of the

village to student groups. It leases part of another warehouse nearby to run a small café, with an adjoining exhibition area, helping to fund their events and research. With the landlord’s permission, they also

cleared their building’s rooftop to install an organic vegetable garden, selling produce to city cafés. Meanwhile, the Mullae district is now inhabited by more than 170 artists. Unlike recent art precincts being planned by municipal governments around the region, classifying art in the realm of cultural industries, Mullae’s artists and independent spaces remain part of the urban fabric on their own terms.

When we met at the LAB39 office late last year, Kang discussed

the distinct relationship the group has to the area. LAB39 includes ten core members but has a network of collaborators in East Asia, Europe and South America. Besides their research projects, many members—including Kang—produce their own artwork, while being involved in social and cultural activism. Kim points out bunk beds in one corner of the office that were built by the group, which serve as what she calls an “autonomous residency program.” Kang explains: “In general, residency programs around the world are competitive; we

don’t like competition. We want to work with our network, through contacts from friends, or friends of friends of friends! Sometimes artists overseas send us a request [to come here], other times we invite the artist.” In Ichimura’s case, she knew about Kim Kang’s work on squatting and contacted the Lab, which is where, during her residency, she met Woofer Ten’s Lee Chun Fung.

For their current research project, dubbed “Squat Geography

Information System,” the Kims are trying to identify which

government-owned buildings in Seoul are not being used and why— information that is not usually made public. Since 2007, they have produced three reports of urban research about Seoul, as well as a book summarizing their findings for a more general public, all of which were published in Korean and hence aimed at enriching the local scene rather than making Seoul, for example, the subject of an international project. As Kim says, “If we find some space, this space is a public space, it’s paid for by our money [i.e., tax money], so we have a right to use it”—or, at least to have a say in how it should be used.

The model for this kind of research readily translates to other

metroplitan areas that similarly live in the shadow of urban renewal. So when the Kims were “artivists in residence” at Woofer Ten in mid-2011, participants at their squatting workshop quickly identified the former Oil Street Artist Village—a large complex on prime land overlooking the harbor that has sat vacant for a decade after its resident art spaces were relocated to the Cattle Depot in a more remote part of Kowloon—as a prime site for a symbolic intervention.

The relevance of these spaces, their activities and relationships, has quickly gained notice. The artist-run VT Artsalon, in Taipei, recently published a book titled Creating Spaces – Post-Alternative Spaces in Asia (2011), featuring Woofer Ten, along with 20 other regional spaces, including Tokyo’s 3331 Arts Chiyoda, Alternative Space Loop in Seoul, Green Papaya Art Projects in Manila, and quite a few in Taiwan.

Differentiating these start-ups from earlier alternative exhibition

venues, in the Taiwan context, artist and VT Artsalon consultant Yao Jui-Chung writes: “The biggest difference between a ‘post-alternative space’ and a commercial gallery or art foundation is that a postalternative space places artists at its core to maintain experimentation, independence, academics and flexibility . . . [Being] young, free and open-minded are its greatest assets, since they can flexibly shuttle between the reality and the ideal.”

While the various initiatives in Creating Spaces address similar civic concerns, each operates on its own terms. Woofer Ten, for example, is government funded and housed in a government building; yet on the strength of its management, it shares a close relationship with both the more avant-garde position of LAB39 and the consciously “outsider” status of Ichimura. Perhaps, then, the hardware—the structure—of such spaces no longer predetermines their character. This might explain why such a generic term as “space” seems appropriately potent

as a catch-all designation for groups that, if nothing else, make no

commitment to the “bottom line,” or to specific art-making agendas.

Are they idealistic? Yes. But, these young spaces might argue, their cities and lives are being shaped by powerful ideals, of a neoliberal variety, that are no more or less logical in reality. Talking over the chatter of regular customers one afternoon in January, in an old yum cha restaurant next door to Woofer Ten, Lee Chun Fung, and founding director, Jaspar Lau, explained the history behind this atypical art space-cum-community-center, which relies on annual grants from Hong Kong’s Arts Development Council.

Originally a Chinese herbalist, the Woofer Ten premises became the “Shanghai Street Artspace” (still its official name) based on a proposal by local arts organizer Howard Chan. Over the ensuing decade, it was managed by various arts groups or individuals, often as an exhibition venue, even offering art courses at one stage; yet by the time it became available for proposals again in 2009, notes Lau, “the local art scene had changed, people were talking about the community.” Artist Luke Ching, known for works that directly engage city life, saw this as a chance to create an art space focused on process rather than outcome, situated in the middle of an old neighborhood.

Woofer Ten was registered that year as a nonprofit organization,

with a dozen “members,” including Cheng Yee-man and Clara

Cheung (who together established the sister space C&G Artpartment in nearby Prince Edward around the same time), Cally Yu, Wen Yau and current director Lee Chun Fung. The space was intended not only for producing contemporary art in a permanent local context, to familiarize the community” with conceptual art practices and practitioners, but it also hoped, by encouraging members to produce on-site, to challenge studio-based (“self-orientated,” says Lau) practice, to confront the everyday, and not simply as an abstract ideal.

“The advantage” of being in Yau Ma Tei, Lau says, “is that you are

already in the community; people get to know you day by day.”

Subsequent projects have blurred the lines between audience and participant, exhibition space and community center. When a nearby flower plaque master, Wong Nai Chung, was forced out of his home due to urban renewal, Woofer Ten used their “Artist in Residency” program to accommodate him long-term in their space, designating him “Flower Plaque Master in Residence.” When members, Wong Wai Yin and her husband Sheung Chi Kwan returned from their respective New York residencies, Wong turned Woofer Ten into a subsidized espresso café. Serving patrons herself, Wong funded the “project” with

part of her grant—thus sharing, she says, both the café experience of New York at a discounted price, and, indirectly, the generously taxpayer-funded residency grant. In this way, many of

Woofer Ten’s projects parody the prevailing system of exhibitions, exhibition spaces or grant proposals in Hong Kong—diverting official resources into a mixture of locally contingent needs and artistic experimentation, through the relative autonomy of an art space.

Since its inception, Woofer Ten has also undergone a subtle shift

in its direction. Whereas founding director Lau and instigator Luke Ching represent the generation that was just coming into adulthood when the 1989 June Fourth student movement took shape in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, sparking simultaneous marches and benefit concerts in Hong Kong, 28-year-old Lee is from what has come to be dubbed as the “post-80s,” referring to a social movement whose main actors, many of them artists, were born after 1980 and are thus the last generation to grow up under British rule, and in some senses the first to experience an arbitrarily imposed national identity in their formative years (Lee recalls suddenly having to learn Mandarin and sing the national anthem at secondary school, for example). The post-

80s movement coalesced in December 2006, around opposition to the proposed demolition of Hong Kong’s old Star Ferry Pier and clock tower, at Edinburgh Place. Not without irony perhaps, it was a threat to the territory’s colonial architecture that sparked a sense of losing local heritage and identity, amid rampant redevelopment and increased mainland influence in Hong Kong life.

Lee considers the last stand of the post-80s to be the 2009 “Choi

Yuen Tsuen Woodstock: An Arts Festival among the Ruins.” Free and public, the festival comprised music, exhibitions and performances organized in collaboration with local residents to protest the XRL high-speed rail-link (connecting Kowloon with mainland China’s express train between Shenzhen and Guangzhou). The government had announced, in January 2010, that it would be built through the Choi Yuen village and farmlands in the north of the territory, at a public cost of over HKD 66 billion (USD 8.5 billion), and contracted to a private company that is also a major property developer. There was added irony in the fact that the train will stop in the middle of another expensive project, the West Kowloon Cultural District, developed at a cost of HKD 21.6 billion (USD 2.8 billion) so far, to an unsupportive public. Over two days, almost 2,000 people joined Choi Yuen residents,

despite knowing the fate of the site had already been sealed.

Such community-based or artivist practices are not only a response to changes in urban politics and the privatization of city development; they also represent a shift in the oppositional relationship of aesthetics and politics, a central problem of modernity.

In the 20th century, societies in which this opposition was overcome, through its apparent denial or union, were totalitarian in nature. But, unlike the historical avant-garde that sought to keep the two spheres apart by alternately

choosing to radicalize in either the aesthetic or the political direction, something different is at work among artists today. With bursts of collective energy, in either or both of these directions, artivists can, by virtue of the flexibility of their individual practices and collective organizations, as Yao Jui-chang suggested, move between their reality and an ideal. This contingency is more potent than any one medium, because it lies in the ability to think differently. Call it imagination. So, while the post-80s generation in Hong Kong has since lost its steam and fragmented, its members, such as Lee Chun Fung, have

taken their ideals in different directions. Some have moved into radio, others into sustainable farming. Lee is now at Woofer Ten. In Seoul, Kim Kang also spoke of her preference for change and mobility; and no doubt Mullae Artist Village will run its course and other paths will be explored. All are busy looking for ways to create or contribute to “the future”—which, after all, is always already, alternative.